by David Otte/photos by the author

by David Otte/photos by the author

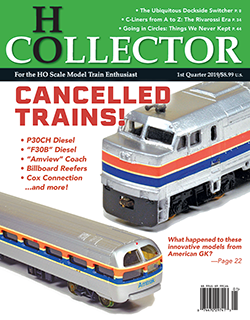

While that seemingly ever-present bulldog-nosed diesel referred to simply as the “F-unit” stands out in most current HO scale enthusiasts’ minds as the great de facto starter train set locomotive, which admittedly provided the proverbial spark for so many model railroaders, there was actually another equally ubiquitous model that preceded the famous Electro-Motive design in this inspirational role — the Dockside Switcher. Also known as “Little Joe” and based on the Baltimore & Ohio’s (B&O) C-16 class steam locomotive, the stubby Baldwin-built 0-4-0 with its large tank-wrapped boiler stands out in stark contrast to the sleek streamlined carbody of the F-unit. However, for the initial generation of HO scale modelers that arose following World War II, the Dockside represented the motive power of the day in a compact format suitable for establishing a small home layout.

During a production period that spanned more than seven decades, hundreds of thousands of these diminutive switchers were produced for separate sale, as well as heading up many starter train sets. As such, the Dockside greatly influenced the popularity of the scale in its most formative years. While Gordon Varney’s 1941 introduction of a 1:87 die-cast metal kit of the Dockside, joined later by renderings fabricated in brass/metal by Pacific Fast Mail-Sakura and Gem Models, certainly played an important part in building the 0-4-0 tank engine’s stature during the early days of HO gauge, this article will primarily examine the ready-to-run plastic offerings that followed, starting in the mid-1950s, by the likes of AHM, IHC Hobby, Life-Like, Pemco, Revell, Rivarossi, and Varney.

A post-1954 Varney Dockside example, complete with original packaging. The 0-4-0 came ready-to-run and featured an injection-molded shell mounted on a die-cast metal chassis. Wire-formed handrail installed along the boiler and the metal side rods themselves were the only separately applied details included. The modeler did have an option of coupler types to choose from, though, including Varney’s dummy knuckle, as well as its patented Automatic Coupler (no. 2483), which is present on the rear of this sample. A NMRA-design horn hook-type coupler has been mounted on the pilot.

B&O’s Little Joe

At the turn of the 20th century, the B&O had a rather interesting operation going on in its Baltimore waterfront district. Dating back to 1831, track had been laid down the center of busy Pratt Street between the railroad’s Mt. Clare Shops near the intersection of Poppleton Road and east to President Street, where it connected with the Pennsylvania Railroad’s line to Philadelphia. Early on, it had served as a main line connection for the B&O, but by the late 19th century, the Pratt Street run was an important thoroughfare for the many industrial plants and the harbor straddling either side of the track. Initially, horse-drawn rail cars were employed, but by 1890, a tiny 0-4-0 tank engine, B&O class C-6 No. 31, was on the job shuffling freight cars between the piers and the manufacturers lining Pratt Street. In an effort not to scare the horses still being used to haul wagons and coaches down the street, the locomotive was completely enclosed within a cab body, so only its wheels were visible— much like a streetcar, with which the horses were better acquainted. An early city ordinance also required that the railroad provide a crossing guard on horseback to ride ahead of the steam locomotive, sounding a horn, to warn horses and pedestrians alike that a train was coming, a practice that continued until World War I.

It was about this time that B&O management approached Baldwin Locomotive Works in search of a replacement for the old No. 31. In 1912, the builder outshopped four new C-16 class 0-4-0 saddle tank locomotives, Nos. 96–99 (and the last 0-4-0 steam switchers to be constructed for the B&O), expressly designed for service on Pratt Street, where tight radius curves and close clearances encountered on the sidings servicing the many warehouses were the norm. With drivers measuring 48 inches in diameter and a short wheelbase of only 84 inches, these 29-foot, 1-inch-long Little Joes, as the crews began to call them, could negotiate curves of 50 degrees at normal speed and 82 degrees at slow speed. Erected as oil burners, the 0-4-0s could hold 650 gallons of fuel in the tank situated behind the cab and their saddle tanks had a capacity of 2,000 gallons of water. Equipped with 19-inch x 24-inch cylinders, an operating boiler pressure of 180 pounds, and a weight on drivers of 120,000 pounds, these little Dockside locomotives could produce a 28,800-pound tractive effort. For the day, these tank engines were rather modern in design too and included Walschaerts valve gear, Ragonnet power reverse, and American driver brake.

Comparing the drive mechanisms of Rivarossi’s Dockside (left) with Varney’s model (right), one will notice the Italian manufacturer chose to power the rear drive axle, while the made in the USA Little Joe is powered via the front axle. Note both models included additional weights in the boiler shell to assist in their tractive effort, which typically rated about 20 pieces of rolling stock on level track. While Rivarossi included a headlight feature on its models, the early Varney renderings did not.

Within their first decade of service, it was apparently determined that only two Little Joes were required for service on Pratt Street and by 1926, Nos. 96 and 99 had been rebuilt as conventional coal burners with new cabs and slope back tenders (re-classed C-16a, both retired by 1945), and assigned work in the Philadelphia area. Nevertheless, 97 and 98 carried on, eventually working a day shift at the Mt. Clare Shops and only coming out at night on Pratt Street, after the traffic had died down, to service the businesses and piers along the Baltimore waterfront.

In 1950, the 0-4-0s were renumbered 897 and 898, but, shortly thereafter, were replaced by a pair of 400-hp General Electric diesels, and soon the Docksiders met the scrapper’s torch in 1951. The Pratt Street shuffle would continue on until 1972, at which time the dwindling operation had been handled by a single Alco S-1 diesel switcher…